Warum Gen-Editoren wie CRISPR/Cas eine Chance für Neurowaffen sein könnten

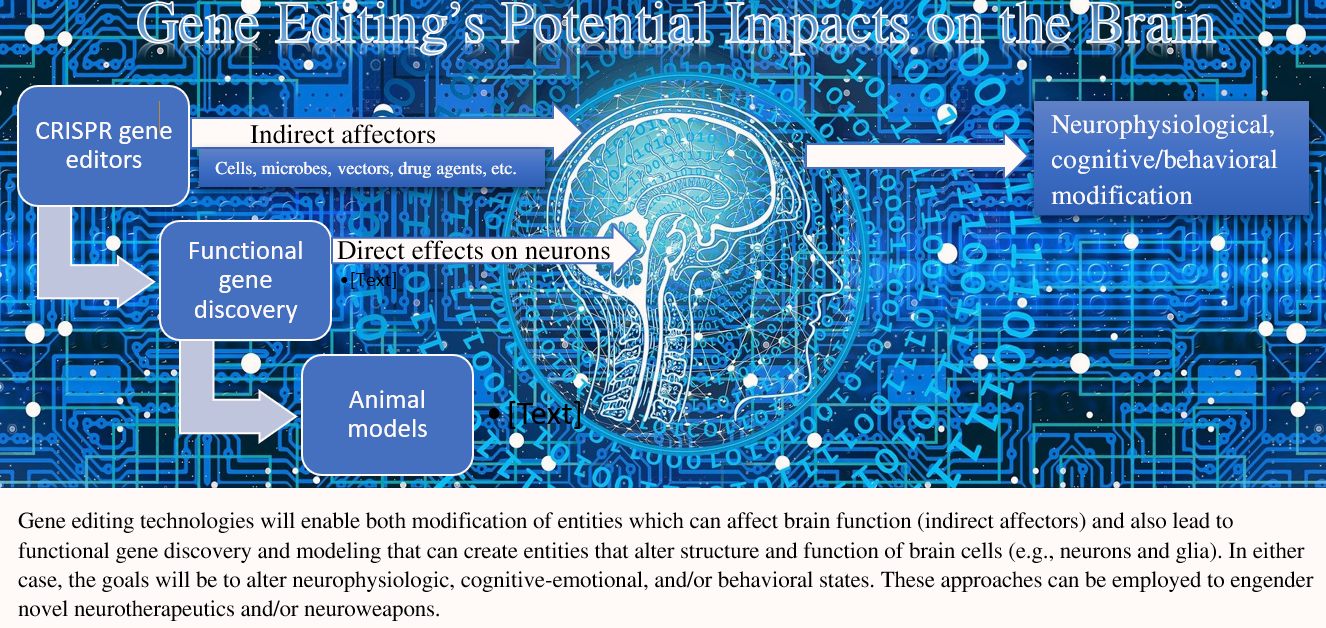

“In diesem Jahr findet die achte Überprüfungskonferenz (RevCon) des Übereinkommens über biologische Toxine und Waffen (BWÜ) statt. Gleichzeitig werden durch die laufenden internationalen Bemühungen, die komplexen neuronalen Schaltkreise des Gehirns weiter und tiefer zu erforschen, nie dagewesene Möglichkeiten geschaffen, die neurologischen Prozesse des Denkens, der Emotionen und des Verhaltens zu verstehen und zu kontrollieren. Diese Fortschritte sind sehr vielversprechend für die menschliche Gesundheit, aber es wurde auch auf das Potenzial ihres Missbrauchs hingewiesen, wobei sich die meisten Diskussionen auf die Forschung und Entwicklung von Wirkstoffen konzentrieren, die unter die bestehenden Verbote des BWÜ und des Chemiewaffenübereinkommens (CWÜ) fallen. In diesem Artikel erörtern wir die Möglichkeiten des doppelten Verwendungszwecks, die durch den Einsatz neuartiger biotechnologischer Techniken und Werkzeuge – insbesondere neuartiger Gen-Editoren wie CRISPR (clustered regular interspaced short palindromic repeats) – zur Herstellung von Neurowaffen gefördert werden. Auf der Grundlage unserer Analysen gehen wir davon aus, dass die Entwicklung gentechnisch veränderter oder künstlich hergestellter neurotroper Substanzen mit anderen gentechnisch hergestellten Therapeutika schnell voranschreiten wird, und wir behaupten, dass dies ein neuartiger – und realisierbarer – Weg zur Schaffung potenzieller Neurowaffen ist. Vor diesem Hintergrund schlagen wir vor, die derzeitige Kategorisierung von waffenfähigen Werkzeugen und Substanzen zu überdenken, um bessere Informationen zu erhalten und eine nachvollziehbare Politik zu entwickeln, die eine bessere Überwachung und Kontrolle neuartiger Neurowaffen ermöglicht.

Die Autoren erörtern die Möglichkeiten des doppelten Verwendungszwecks, die durch den Einsatz neuartiger biotechnologischer Techniken und Werkzeuge – insbesondere neuartiger Gen-Editoren wie CRISPR (clustered regular interspaced short palindromic repeats) – zur Herstellung von Neurowaffen gefördert werden. Sie gehen davon aus, dass die Entwicklung gentechnisch veränderter oder künstlich hergestellter neurotroper Substanzen mit anderen gentechnisch hergestellten Therapeutika schnell voranschreiten wird, und behaupten, dass dies ein neuartiger – und realisierbarer – Weg zur Schaffung potenzieller Neurowaffen ist.”

[…]

“In der Zwischenzeit werden wahrscheinlich indirektere Mittel zur Manipulation des Gehirns und des Verhaltens entwickelt werden. Das ”Neurohacking” wird zunehmen, und die Biotechnologie, wie CRISPR/Cas und neuartige Gen-Editoren, wird Werkzeuge zur Verfügung stellen, um die Produktion neuartiger Neuroagenten mit doppeltem Verwendungspotenzial zu realisieren.

tential. Die bloße Anerkennung dieser Tatsachen ist jedoch nicht ausreichend. Es ist von entscheidender Bedeutung, ein tieferes und umfassenderes Verständnis der Möglichkeiten zu erlangen, wie genetische Wege zur Veränderung menschlicher kognitiver und verhaltensbezogener Fähigkeiten für den doppelten und direkten Einsatz als Neurowaffen genutzt werden können, um

die Formulierung von Strategien auf der Grundlage dieses Verständnisses und die Überwachung des Einsatzes dieser Technologien in den verschiedenen Entwicklungs- und Anwendungssilos, um sowohl präventive als auch eher vorbereitende Möglichkeiten zu schaffen.”

Plain numerical DOI: 10.1089/hs.2016.0120

DOI URL

directSciHub download

Show/hide publication abstract

Show/hide publication abstract

Plain numerical DOI: 10.1057/s41292-018-0121-4

DOI URL

directSciHub download

Show/hide publication abstract

Plain numerical DOI: 10.4324/9780429447259-6

DOI URL

directSciHub download

Plain numerical DOI: 10.1057/9781137381828

DOI URL

directSciHub download

Show/hide publication abstract

Plain numerical DOI: 10.1057/9781137381828_6

DOI URL

directSciHub download

Show/hide publication abstract

Show/hide publication abstract

Plain numerical DOI: 10.1057/9781137381828.0013

DOI URL

directSciHub download

Show/hide publication abstract

Plain numerical DOI: 10.1093/lril/lru009

DOI URL

directSciHub download

Show/hide publication abstract

Show/hide publication abstract

Plain numerical DOI: 10.31374/sjms.86

DOI URL

directSciHub download